Anna Lublina

At PlySpace, Anna Lublina has explored dough as a sculptural material and performance partner through their multidisciplinary project Leavening Agents. Their creative research has drawn from local bread recipes and the wetland ecological systems prominent in Muncie. Guided by the idea that dough is a living organism (a bubbling combination of flour, water, and yeast!), Anna has investigated the way dough responds when in relation to other ecological systems, like grasslands, riverbanks, and skin microflora. Border ecologies–– the place where two ecologies meet–– is the most healthy and diverse in the world. Anna uses these teachings from the natural world to consider the ways social borders in Muncie –– neighborhood borders, racial borders, socio-economic borders, religious borders–– are fertile grounds of bio and cultural diversity. This research unfolds in a series of sculptures, texts, photographs, performative gestures, and social encounters.

Piece of braided bread on grass at the Red-tail Nature Preserve (shot by Melissa Joy Livermore)

A landscape of bread and natural materials (shot by Melissa Joy Livermore)

Anna Lublina (they/she) is an interdisciplinary performance maker and educator focused on building mutually beneficial relationships between humans, objects, and environments in their work and life. As the child of a Soviet Jewish immigrant, they are drawn to diaspora as a creative format. They reject disciplinary borders to instead explore the mutability of structure, linking social practice, object theater, dance, music, and text to create installations and performances that imagine more caring, equitable futures.

Anna’s work has been presented at various venues throughout New York City, including St. Ann’s Warehouse, Judson Church, the 14th St Y, Center for Performance Research, and The Old American Can Factory, among others. Anna has been supported by fellowships and residencies such as the Annenberg Helix Fellowship at Yiddishkayt (2020-2022), LABA Fellowship at the 14th St Y (2019-2020), the St. Ann’s Warehouse Puppet Lab (2018-2019), SDCF Observership (2019-2020), the Blueprint Fellowship by COJECO, an organization that supports the Russian-speaking Jewish (RSJ) community (2019).

Anna recently started a Masters degree in Choreography and Performance at the University of Giessen in Germany. They are really thrilled to be here in Muncie making work in this strange time.

Video shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

Video shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

Leavening Agents at the border

Bread assemblage with bricks by me and shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

“I, like many of you, slowed to a halt in March of 2020. Everything on my calendar suddenly wiped. I have to admit that I was relieved at first. This was the first instance in years that I was in possession of time—a rare and delightful commodity in my life! I had empty days that I could fill with TV shows, walks in the Greenwood cemetery, and… bread-baking. Yes, like many Americans, I too was summoned by the pandemic gods to join in baking sourdough bread!”

“Rock and water

Wind and tree

Bread dough rising

Vastly all

Are patient with me.”

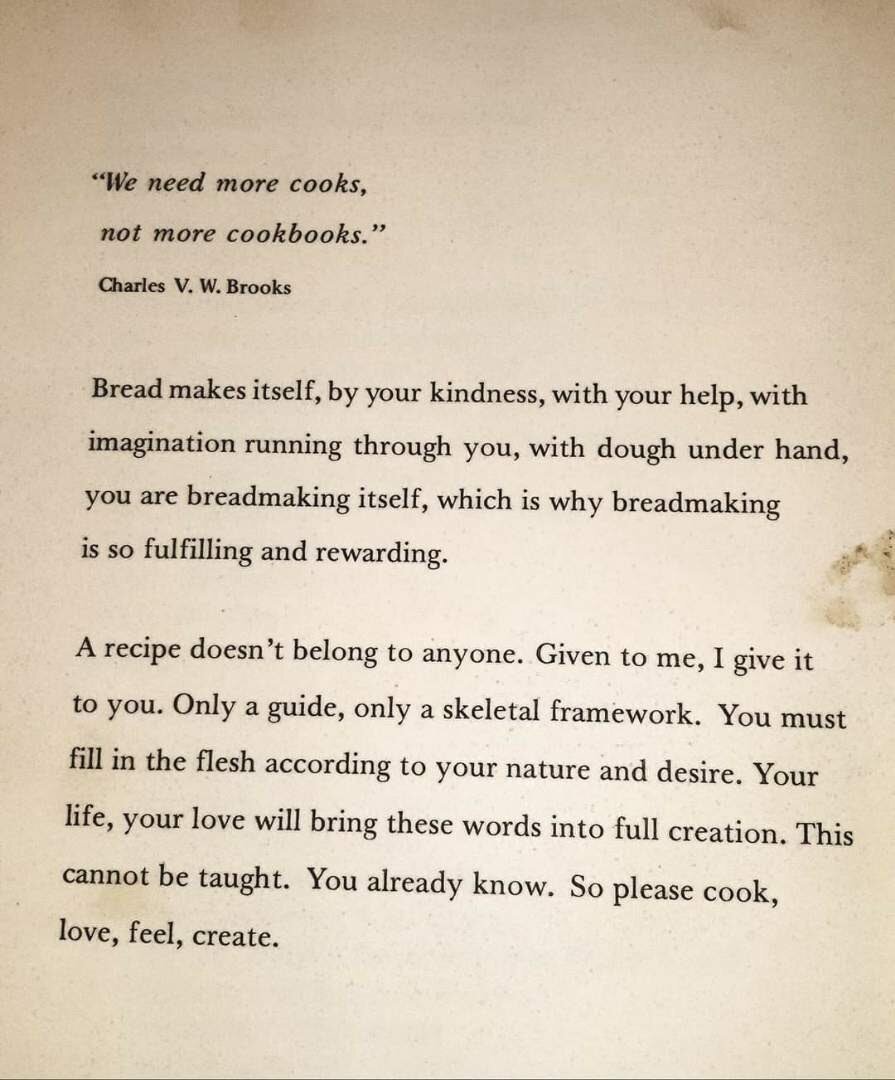

“This is not the first time sourdough has become popular in the US. According to Wikipedia, the revival began in 1970 upon the release of the Tassajara Bread Book. This book was written and compiled by “Kainei” Edward Espé Brown, an American Zen teacher at the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. Bread practices and Zen practices: an odd pairing but one that makes sense.

Baking bread has long been connected to time, breath, space, patience, and care –– practices key in Zen Buddhism. Bread does not adapt to us. Instead, we must learn to wait for it to rise on its own time.”

“I asked my dear friend Julian for some of his sourdough starter, and he walked his dog, Bill, over to my house to drop off a small tupperware of it. I wasn’t simply interested in baking because I had the time—I was also stressed, and I needed an outlet. Like many of you, anxiety had begun to consume my life as sirens wailed through Brooklyn, and I wanted to feel like there was something I could control. As Ashley (food conservation specialist and Muncie resident) said to me so articulately: “When uncertainty in the world spikes, so does food preservation and bread baking.” We were all hungry for stability. I looked for this in the sources of my food: in the land, air, water, and even in my own body.’”

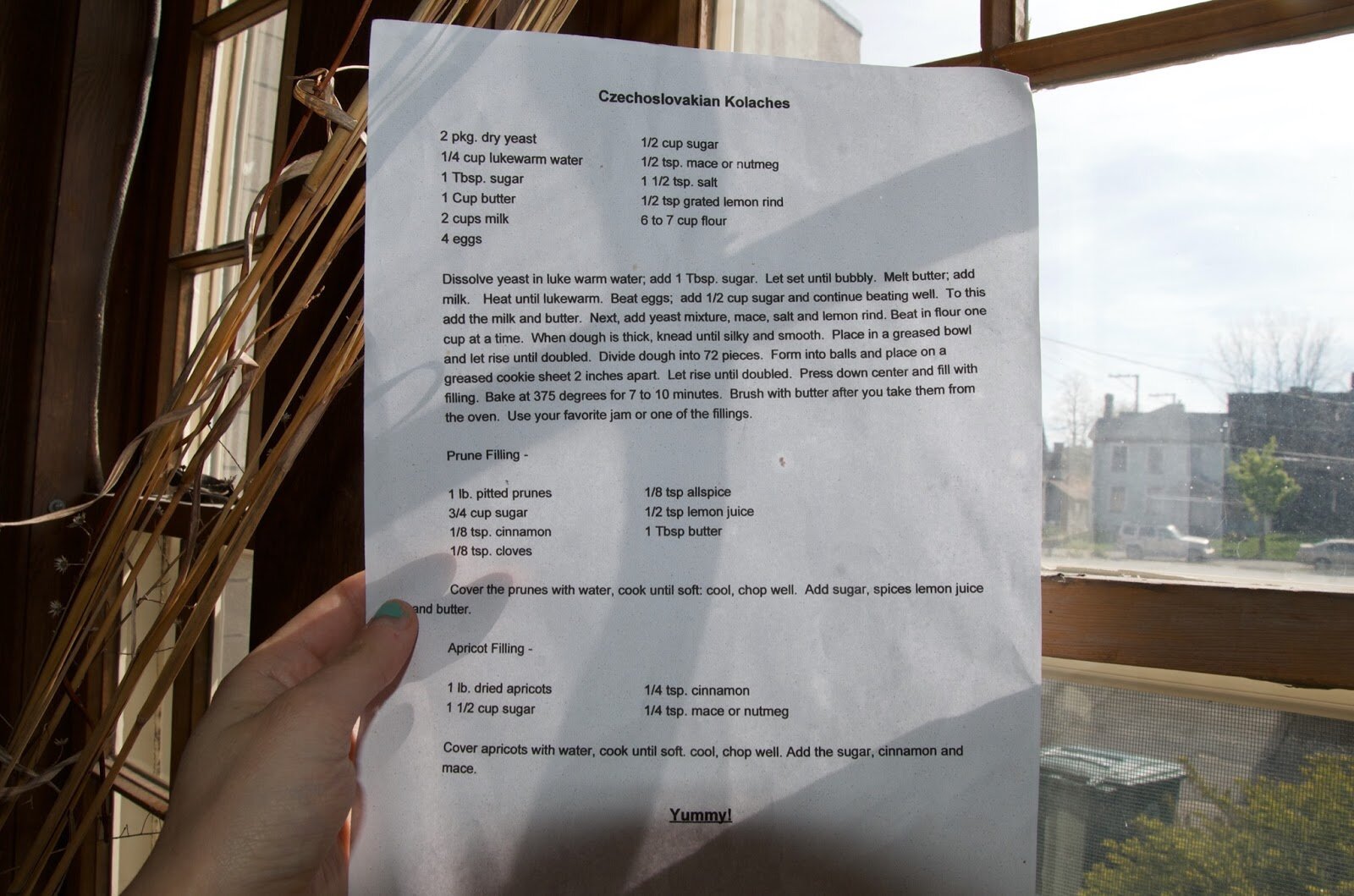

Cookbooks bought at White Rabbit Used Bookstore

“Kneading the dough was harder than I expected. Tending to the sourdough was even harder. How was I supposed to remember to feed it everyday? It felt like a real partnership. I had to tend to its needs alongside my own. Our skin touched everyday; we fed each other; we became a part of each other. You may think I’m being poetic, but I’m not. Microbes from my body were a part of the ferment (sourdough), changing the microbial ecosystem. Sourdough is alive. It is a microbial culture of living and dying beings.”

“Long soft enzymes take hold

Find a home

Flour and water, warm, sweet

Saccharomyes cerevisae

It’s slow how it goes

Wild yeast finds us

In this home

Lactic acid bacteria

Rod shaped

In this home

A hand, a spoon, an interface

A drama ensues

A drama of digestion, decay, gas

A fungus kingdom

A leavening power”

Diagram of Sourdough Science by Anna

Kirk Robey at his home outside of Muncie

“Sourdough is an ecology of creatures that includes me and you. Studies show that an identical starter will change after being used just a few times by a different person or in a different place. Kirk Robey, the Bread Science Instructor at Ivy Tech, pointed this out to me when I first begged to visit his flower farm outside of Muncie and take a bit of his 15 year old starter. Even though his sourdough is no longer his and has quite literally become mine, I was happy to take a little souvenir of his bread wisdom.”

Find out more about the research from Dunn Lab.

“This change in the sourdough’s microbial ecosystem happens because the air is different, the flour is different, the surface is different, and the hands are different. In Korean, there is a phrase used to describe this, “son mat,” which literally means “hand taste.” Studies also show that the microbial cultures in the bread match the cultures on the bakers’ bodies––which means that the sourdough becomes a part of our microbe too.

Emily Johnson, a History Professor at Ball State, told me that when she exchanged cake and bread with her neighbors this year, it was a way of exchanging touch. She’s technically right. Her body was a part of that bread’s microbiome and when her friend ate it, their microflora were united, mixed, a yeasty, bacterial hug.”

Photo of Anna washing with dough shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

Photo of a baked piece of sourdough yeast shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

“Even though I came here to study the baking culture, the first thing I did in Muncie was find the famous wetlands. Now I visit the John Caddock Wetland Nature Reserve and Red-tail Nature Preserve every few days. They are my favorite places here, second only to the White River. Everytime I leave the Plyspace building for a walk, I find myself at the river. I am drawn to the beauty and vibrant sociality of the river—even as I feel the painful ways it divides this city up across socio-economic lines.”

The border between the Whitely and Granville neighborhoods, shot by Anna

The border between the Industry and Southside neighborhoods, shot by Anna

Since arriving in Muncie, I’ve become obsessed with the idea of borders between ecosystems: the river bank, where the forest and the ocean meet, between the tall grasses and wet soil beneath the Ash trees; where the dough and my skin touch; the place in time where I can’t remember the word in English so I say it in Russian; the railroad that separates one neighborhood from another. The spaces between ecologies are not gaps—they are a space of mingling. Borders are the healthiest ecosystems in the world because they are the most diverse. This reality doesn’t quite square with the image of walls I see when I think of a border. Maybe the better image is a bridge. Border ecologies are bridges from one culture to another.

Border between bread and grass and river, shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

Border between dough and my skin, shot by Melissa Joy Livermore

“For me, bread is a border ecology and a bridge. In my time here in Muncie, I tried to find bridges in the community through bread.”

“It is something that is (usually) politically neutral (even though, of course, we know that neutrality doesn’t exist). Still, bread felt like an area where we could practice “with-ness” in a place that holds many divides. I collected recipes, stories, and sourdough starter from community members all over the city. I tried many of their recipes and distributed them to various friends and acquaintances made over my time here. I tried to create a baking exchange with folks from North Muncie, South Muncie, Whitely, Ball State.

Unfortunately, the bread exchange never came to fruition. I discovered that connecting people across borders is difficult. In natural ecosystems or in sourdough cultures, coexistence, mutualism, and diversity feel so easy. Why is it so hard for humans? Even when diversity has been proven to be so healthy?

While at Plyspace, I will host a social gathering where I have invited the community to chat, eat, honor and exchange different kinds of ecosystems by the river. Everyone is to bring a baked good, a fermented food, mushrooms, roses, or whatever one is called to. This will be an attempt to connect with new people, bread, and the natural ecosystems of Muncie.”

Baking Swedish Limpa Bread with Jamie-Sue Ferrell, shot by Anna

Shared Recipes and Words of Wisdom

PlySpace is a program of the Muncie Arts and Culture Council, in collaboration with the Ball State School of Art, Sustainable Muncie Corp, and the City of Muncie. PlySpace is funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. The PlySpace Gallery is located at 608 E. Main Street, Muncie, Indiana, and is open for special exhibitions and events. Please check the PlySpace events page for details.